Original images held by the Harvard-Yenching Library of the Harvard College Library, Harvard University

Summary written by Benjamin Landauer (Ph.D. Candidate, Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, Harvard University)

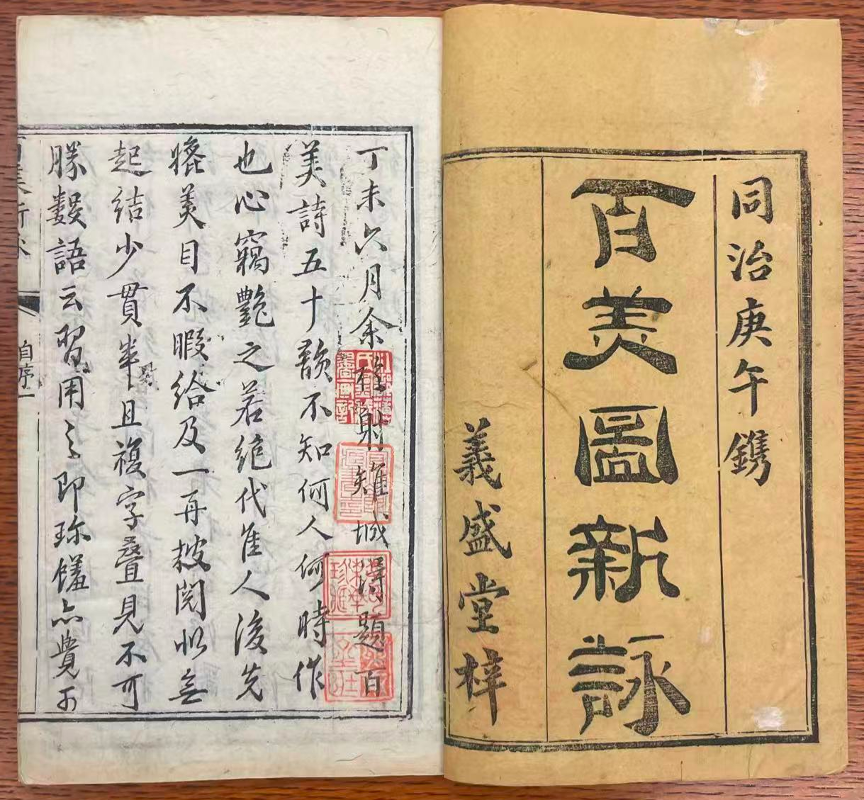

The New Pictorial Verse Records of the Hundred Beauties百美新詠圖傳 is a unique folio hailing from late imperial Chinese publishing culture. Compiled in 1787 by Yan Xiyuan 顏希源 (fl. late 18th cent.) and illustrated by Wang Hui 王翽 (1736-1795), the book is a catalogue offering poetry, painting, and historical anecdote for 103 women hailing from Chinese history and mythology.[1] A fascinatingly layered text, the Yenching library is home to an edition printed in the ninth year of the Tongzhi reign period (1870, 同治庚午), string-bound in four volumes with minor page restorations.

Title page (right) and the beginning of Yan Xiyuan’s preface (left).

The first volume is entirely paratextual material, containing ten prefaces from contemporaries rendered in a nice variety of calligraphic styles, followed by a series of preface poems by nineteen different authors. Yan Xiyuan himself wrote the first preface, wherein readers find that Yan once encountered an anonymous poem of fifty couplets that lauded these hundred women. Yan was so taken aback in wonder by the poem that he invited his friend Wang Hui to paint images for each of the hundred women described in the poetic lines. The inspiration for Yan’s project thus has its origins with an unknown poet.[2] Rather notable here is also preface written by Yuan Mei 袁枚 (1716-1797), widely known for his patronage of women’s literary activities.

Opening the second volume, one encounters the “New Versification of the Hundred Beauties” 百美新詠, ostensibly the poem that Yan had mentioned in his preface. Running five pages in length, this poem affords each of the following hundred entries with a single pentasyllabic line of poetry, followed immediately by an indication of the person about whom it is written. Poetry interpretation practices encourage the reader to approach it as a cohesive work, but the curiously meandering text functions more smoothly as a table of contents for the hundred pictorial entries that follow in third and fourth volumes.

An example from this “table of contents” reads as follows: “Golden lotuses colored with every step / beautiful makeup leaning against a florid balustrade” (金蓮步步彩, 靚粧憑綺閣). The former half of the line is indicated to be about Pan Guifei 潘貴妃 (fl. 5th cent. CE), imperial consort to Xiao Baojuan 蕭寶卷 (483-501); and the latter half is about Zhang Lihua 張麗華 (d. 589 CE), imperial consort to Chen Shubao 陳叔寶 (553-604). Another entry, incidentally the one that the book ends with, are two women of celestially legendary status: “Luckily obtaining the medicine for everlasting life / nothing stops the meeting on the Seventh Eve” (幸竊長生藥, 何妨七夕期). The former is about Chang’e 嫦娥, the moon goddess who obtained the medicine for everlasting life, while the latter is about the Weaver Girl 織女, she who crosses the Milk Way once a year on the Seventh Day of the Seventh Month to meet with her lover, the Herd-Boy 牛郎. The work, at its heart, is a litany of allusions.

Volume two continues with a section entitled “New Verses” 新詠, wherein each of the 100 women listed are described in a full poem. This section follows the ordering of the table of contents. However, immediately following those poems is another section entitled “Collected Verses” 集詠, which is attributed to none other than Yuan Mei. This section does not adhere to the same order of previous material, but is instead miscellaneous and sometimes repetitive verse on various women from the collection.

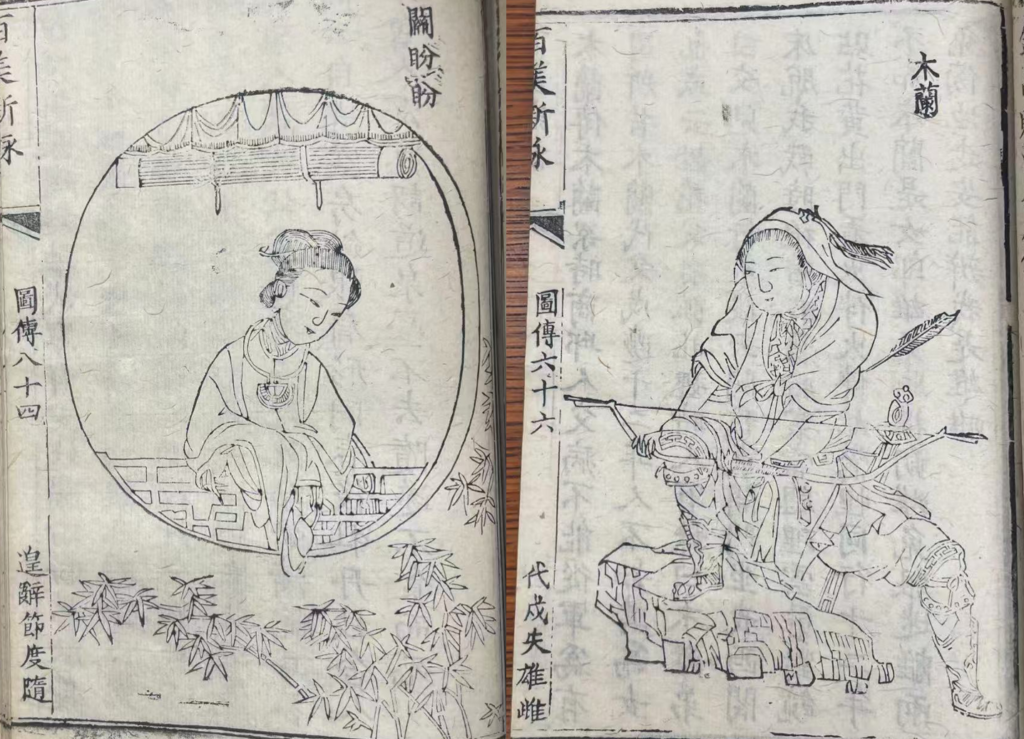

The third and fourth volumes present Wang Hui’s images alongside extant biographies of the hundred beauties. While the biographies are copied directly from well-known sources such as Sima Qian’s 司馬遷 (BCE 145-86) Records of the Grand Historian 史記 or Ban Gu’s 班固 (32-92 CE) Latter Book of Han 後漢書, it is Wang Hui’s images that tend to draw the most attention.[3] Here are the entries for a famous entertainer of the Tang dynasty, Guan Panpan 關盼盼 (fl. 8th-9th cent. CE), and the beloved crossdressing martial figure of the Northern Dynasties, Mulan 木蘭 (ca. 5th cent. CE):

Guan Panpan (left) and Mulan (right)

Perusing the hundred images, readers notice that this edition contains what appears to be an amusing collation error. In the second volume, Yuan Mei’s “Collected Verses” stops abruptly on page 26, with the final column of printing indicating a title that has no poem attached. Yet in the third volume, readers notice that the rest of Yuan Mei’s poems inexplicably appear between the 18th and 19th biographies, picking up right on page 27 where they had left off. Rather than a printing mistake, this is a binding error wherein the final sixteen pages of volume two were accidentally set and bound into volume three.[4]

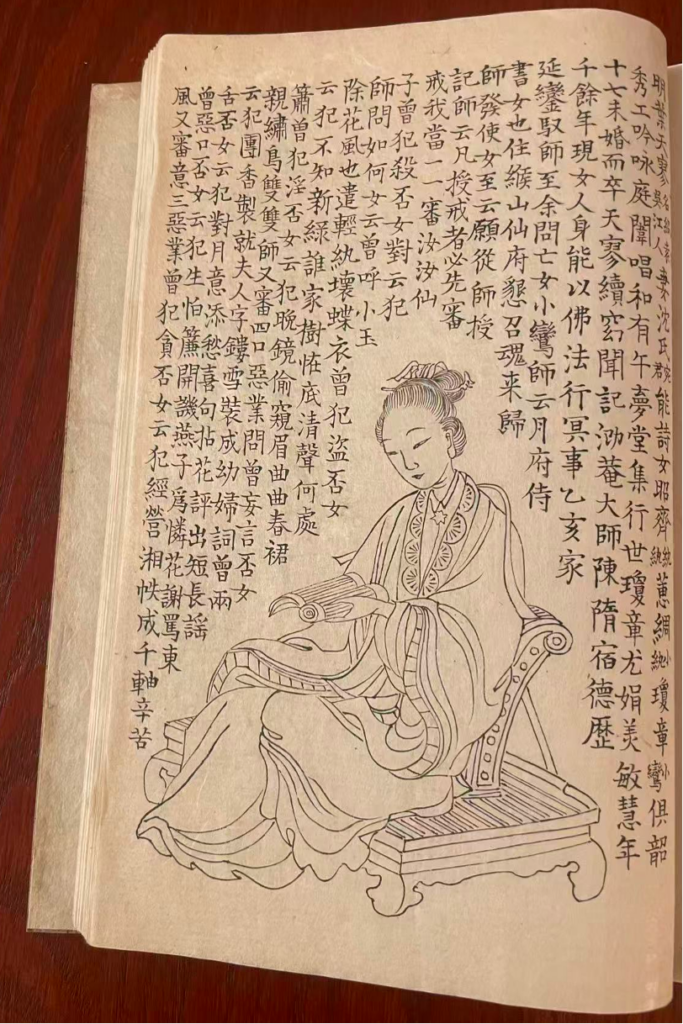

The Yenching Library is also home to another version of the book that gives some insight into its afterlife. Held in the Japanese collection, the single-volume version is a significantly simplified and painstakingly updated version of the older text, datable only to 1885 by a note on page four indicating “eighteenth year of Meiji.” This hand-copied version of the work does away with all of the poetic ephemera found in the first two volumes of the 1787 version, instead taking the standard biographies and putting them directly on the white space over the images. Examine, for example, the entry on Ye Xiaoluan 葉小鸞 (1616-1632):

Entry for Ye Xiaoluan in the Meiji edition

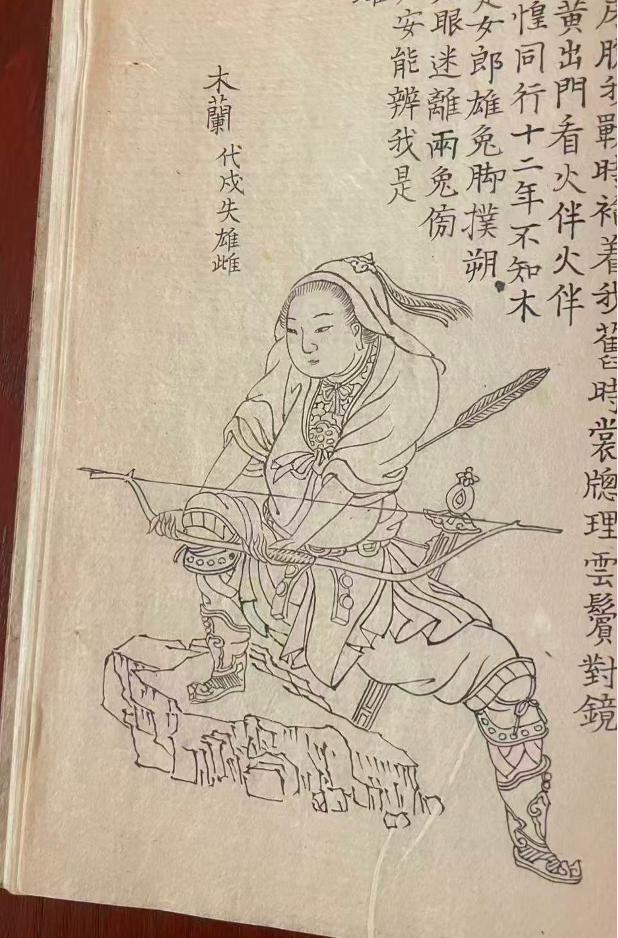

Structuring the text around the image in such a way is much more reflective of the Japanese visual idiom that had come to a flourish in the Edo period. Yet closer inspection of the images betrays the fact that this copyist, known to us only as “Master who Faces the Cherry-Blossom Balustrade” 對櫻軒主人, not only transcribed all of the biographies from the New Pictorial Verse Records of the Hundred Beauties, but also copied every single one of the images to a startling degree of verisimilitude. See, for example, the Meiji version of Mulan:

Mulan in the Meiji edition

We might first notice the sword hilt on Mulan’s left. In the 1870 edition, Wang Hui’s sword hilt pattern is a simpler three-prong design, while the 1885 Meiji version decides to add several more floral petals. Sartorially, we also notice the pattern of cloth just below Mulan’s chin: while Wang Hui’s version is impressionistic, evocative perhaps of rumpled cloth, the Meiji version is instead a detailed schematic that even takes care to add a small tied sash on top of a clear flat-cloth pattern. Even the lines on the rock upon which Mulan steps is rendered with ever-so-slightly different strokes. Indeed, the 1885 date includes the phrase “upon completing a copy” 摹畢, and we today are privy to the results of the copyist’s painstaking and heartfelt work.

The author would like to thank HYL librarians Annie Wang and Yuzhou Bai for their assistance with materials and logistics.

Library Call Information

百美新詠圖傳 (1870 Tongzhi edition, rare book room)

GEN 2261.5 0843

百美新詠圖傳:上下 (1885 Meiji edition, stacks)

(J) PL 2518.8 W65 Y36 1885

[1] For a discussion of edition history, see Zhao Houjun 趙厚均, “Baimei xinyong tuzhuan—jian yu liu jingmin, wang yingzhi xiansheng shangque” 百美新詠圖傳——兼與劉精民、王英志先生商榷. Academics, 2010(6), 102-109.

[2] It is not out of the question that Yan himself wrote that verse and is just pretending that he happened upon them, but that remains a mystery.

[3] For a discussion of Wang Hui’s art in this collection, see Leng Tingzhen 冷庭蓁, “Baimei xinyong tuzhuan chutan” 百美新詠圖傳初探. Art Symposium, 2018(30): 19-37.

[4] The number is 103 because there are three entries that, rather than addressing a single individual, instead treat pairs of women: E’huang 娥皇 and Nüying 女英, legendary consorts of Sage Emperor Shun 舜帝; Feiluan 飛鸞 and Qingfeng 輕鳳, two dancers from the Tang dynasty; and the Qiao Sisters 大喬小喬, famed beauties of the Three Kingdoms period.