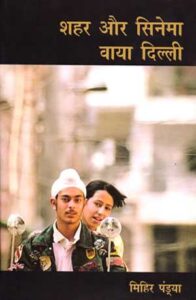

Mihir Pandya

New Delhi: Vani Prakashan, 2011

Reviewed by P.K. Anand (Centre for East Asian Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi)

There has been a good range of academic scholarship on Indian cities and their urbanisms. However, unlike in the West, where there is a multitude of literature using cinema as the lens for urban exploration, there has been a paucity in this regard in India.Therefore, a book in this genre in any regional Indian language, and in particular a study which is analytically grounded and built upon quality sources, is a rare find. Mihir Pandya’s Hindi-language book, Shehar Aur Cinema via Dilli (City and Cinema via Delhi), is one such rare work that demands appreciation. Focusing the lens of Hindi cinema (‘Bollywood’ as it is known to the rest of the world) and interrelating it with the spatial-cultural and political character of a modern Indian city—the national capital of Delhi being the case study—Dr. Pandya’s sociological research has sought to trace the rise of urban space in a post-colonial context. Beginning with the early 1950s nation-building project and socialist ideals of post-independent India (as envisioned by Jawaharlal Nehru), Pandya’s book ranges from the disillusionment that set in due to the failures to realize many of Nehru’s visions in the 1970s—the phenomenon of the ‘Angry Young Man’ representing disappointed and exasperated youth—to the phase of liberalization and marketization combined with the rise of identity politics in the late 1980s to early 1990s. Pandya locates and makes use of such transitions to unravel the intricate meanings associated therein through detailed case studies of various films with story lines based in Delhi.

The author divides the book into three sections, beginning with a general theoretical background providing the historical and socio-political context, thereby anchoring the city as the frame into which the cinematic narratives could be fitted. Titled “The Post-Colonial City and Cinema,” the author discusses the process of urbanization, putting forth concepts of modernity, nationhood, nationalism as well as the rise in the politics of identities, with their relationship to discourses on Indian city space. The introductory section also articulates how the rise of identity politics and the rising aspirations of the marginalized posed serious challenges to the project of nationalist modernization, with the city—in ideational terms—developing within itself multiple visions and contestations of modernity.

Having provided the essential framework, the author moves towards case studies of different films by organizing them under two themes: (1) City of Power and (2) Everyday City, which respectively become the second and third sections of the book. As the national capital, Delhi’s primary identity as the center of power displaces all its other identities, and becomes the symbol of the entire Indian state system; the author is interested in unpacking the power structure of the city, its changing forms and the impact on society. Some of the films under this theme are: Ab Dilli Door Nahi, Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi, Tere Ghar Ke Saamne, Chak De India, and Rang De Basanti. Through the main messages imparted, the portrayal of various characters, the on-screen images/symbols, or the angles of cinematography, the author identifies the various frames and motifs that make up Delhi as a City of Power.

Through the second theme of the Everyday City, the author focuses on the marginalized voices of those who critique the power-centric focus of the city. By studying films that capture everyday life experiences, the author introduces different faces and identities in the city space to readers. Encompassing love, rebellion, relationships, etc., these identities present a subaltern perspective of the city. In doing so, the author seeks to excavate quotidian tales of the city, crafted by the common people and often obscured in ‘grand narratives.’ Whether it is the question of public spaces for romance and issues of safety in Chashme Buddoor, the aspirations of families for a swanky car in Do Dooni Chaar, a plot of land in posh ‘South Delhi’ in Khosla Ka Ghosla, or the legitimacy sought from urban social elites by an ‘illegitimate’ citizen (a professional thief) and a critique on the regressive controls by family in Oye Lucky! Lucky Oye!, these are all images that can be found in the daily kaleidoscope of the city.

Towards the end of the book, Dr. Pandya also provides a complete list of films that are Delhi-based in one form or another. With a fine weave of the cinematic tapestry, providing it as a frame for understanding a city in the Indian socio-political surroundings, the author needs to be commended for this work, which is a real tour-de-force.