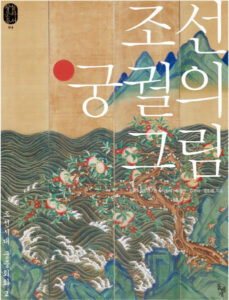

Jeonghye Park, Jeongyeon Hwang, Minki Kang, and Jinyoung Yoon (박정혜, 황정연, 강민기, 윤진영)

Seoul: Dolbegae, 2012

Reviewed by Jaebin Yoo (Ph. D. Candidate, Art History, Seoul National University, Harvard-Yenching Visiting Fellow 2012-13)

What kind of paintings decorated the Korean palaces? How did the king and his family appreciate these in daily life? The Paintings of Chosŏn Palace is the first academic publication to deal with these questions. The book is a collaborative work by four researchers, Jeonghye Park – a pioneer in the field of Korean court paintings – and three other art historians specializing in Korean paintings – Jeongyeon Hwang, Minki Kang, and Jinyoung Yoon. The four authors have taken charge of the field through the “Research Project on the Royal Culture,” directed by Academy of Korean Studies. They have established “king”, “palace,” and “court painters” as the three key words in understanding the court paintings of Chosŏn dynasty (1392-1897), and worked to publish one volume on each theme. The Paintings of Chosŏn Palace is the second volume in the series, following up on The Paintings of the King and the State (2010). This latest publication focuses specifically on the relationship between the palace as an architectural space and court paintings in that specific space, whereas the former publication gave a comparatively wider overview of court paintings revolving around the king.

The Paintings of Chosŏn Palace is composed of four chapters, each written independently by one of the four co-authors. In Chapter 1, Park examines the symbolic meanings and the ritual function of decorative paintings by their themes. Many of these themes have Chinese origins, such as Guo Fenyang’s Enjoyment of Life (郭汾陽行樂圖) and Xi Wang Mu’s Banquet (西王母 瑤池演圖), while some subjects such as the Sun, Moon, and Five Peaks (日月五峯圖) and the Ten Longevities (十長生圖) are the unique creations of Chosŏn. Readers in the Chinese literature and art history fields could also benefit from this discussion of the appropriation and transition of Chinese subjects in Korea. Park concludes after thorough research on almost 200 paintings on 11 themes that the auspicious omen (吉祥) immanent in the most themes is the key to understanding court paintings. In Chapter 2, Hwang deals with the taste and intention of appreciation by the king and royal family by analyzing royal collection catalogues and the kings’ inscriptions on the paintings. According to her research, most appreciation within the court was aimed at the cultivation of the king himself and a wish for the prosperity of dynasty, while pure enjoyment remained the primary impetus for collecting masterpieces in and outside of Korea. In Chapter 3, Kang focuses on the architectural paintings. Most of the two-dimensional art placed in the Chosŏn court were movable – such as hanging scrolls and screens – and thus it is difficult to determine their original locations or settings. The mural painting format, however, was first introduced in buildings such as Heejŏngdang, Taejojŏn, and Kyounghungak in the Changdŏck palace, rebuilt in the western style around 1920. Kang infers the collaboration system of the murals by clarifying the specializations of the 8 artists of 6 murals and their rival or as master-pupil relationships, based on her knowledge of the painting styles of the artists and the modern painting academy. In Chapter 4, Yoon refers to the issue of the dissemination and reproduction of court paintings and its courtly style to Chosŏn’s folk culture. He suggests various aspects of popularization of the courtly theme and style through side-by-side comparisons of court paintings and folk paintings on the same subjects. Moreover, he attempts to reconstruct the situation of circulating court works by tracing the emergence of modern painting markets and the life of a dealer.

In The Paintings of Chosŏn Palace, the authors have attempted to approach court art in four different ways: symbolism, appreciation, architectural quality, and dissemination. However, the results of this research do not quite meet our expectation of clearly reconstructing how paintings were actually placed and exhibited in the palace space. This is partly due to the historical misfortune that in the early 20th century, many of the palace buildings, along with the art works they housed, were destroyed by fire. The nature of the project, which surveys the wide range of royal culture, could be another reason for the abstract nature of this research. The authors have made an exhaustive investigation of paintings, historical documents, and current research, and have decided to embrace them all instead of narrowing their focus down to a few cases. This is as much a strength of the book as it is a weakness. It provides hundreds of color illustrations, including many first introduced works, as well as a vast and well selected bibliography and index focusing on Korean court art. Through the work, the authors have chosen to lay a solid groundwork for the follow-up studies rather than to rush to a conclusion.

What is the visual experience of the Chosŏn palace? The Paintings of Chosŏn Palace cannot provide a complete answer. After reading the book, however, one has a burning desire to learn more about the subject. This book is the most comprehensive and substantial starting point for those wishing to join this important and underdeveloped field.