Waka kanjo & cosmetics. Produced: [17–?] 1 volume : color illustrations ; 28 cm

Original images held by the Harvard-Yenching Library of the Harvard College Library, Harvard University

Summary written by Juhee Kang (Ph.D., Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, Harvard University)

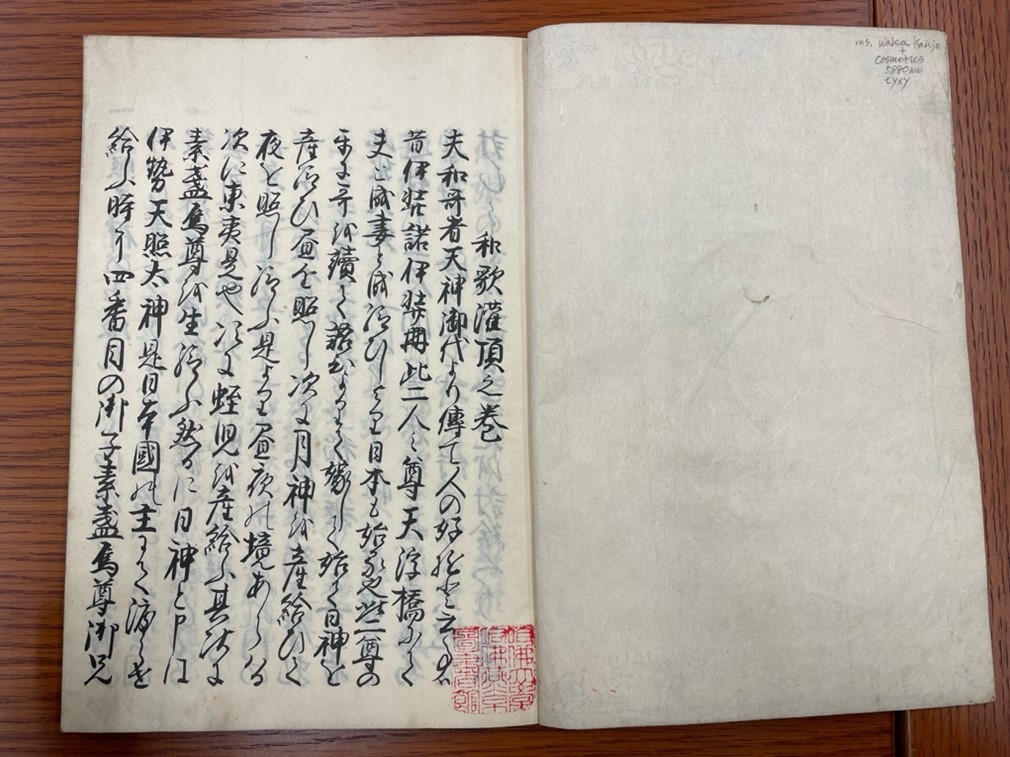

Wrapped in an ornate teal-colored floral silk, Waka kanjō and cosmetics is an eccentric and eclectic manuscript. Just under 60 leaves long, it consists of two distinct parts, each differing significantly in content and style. From the signature inside, we gather that the manuscript was composed around 1683 (using the Tenwa 天和 calendar) and was last handled by someone named Kimura 木村. To appreciate its uniqueness and importance, some context is necessary.

First, what is waka 和歌? Most people familiar with poetry today recognize haiku, a globally renowned form consisting of three lines with a 5-7-5 syllabic pattern. However, even those aware of haiku’s Japanese origins may not know of waka. Literally meaning “Japanese song,” waka originally encompassed all forms of poetry written in Japanese during the Heian period (794–1185). After a thousand years of evolution, waka now refers to a specific poetic form with a 5-7-5-7-7 syllabic structure and is often synonymous with tanka. Haiku evolved from waka in the seventeenth century when poets sought to condense the art of capturing fleeting moments in nature and emotion into a shorter, more concise form.

What then is kanjō 灌頂? Kanjō refers to a baptism-like initiation ceremony for conferring precepts or teachings, deriving from the vocabulary of esoteric Buddhism, which was the religion of the imperial court that peaked in prominence in Japan during the Kamakura period (1185–1333). The term originally described the act of buddhas guiding a bodhisattva who had attained enlightenment. Similarly, waka kanjō, the subject of our manuscript, embodies the coveted guidance passed down through generations of poetic masters to their disciples.

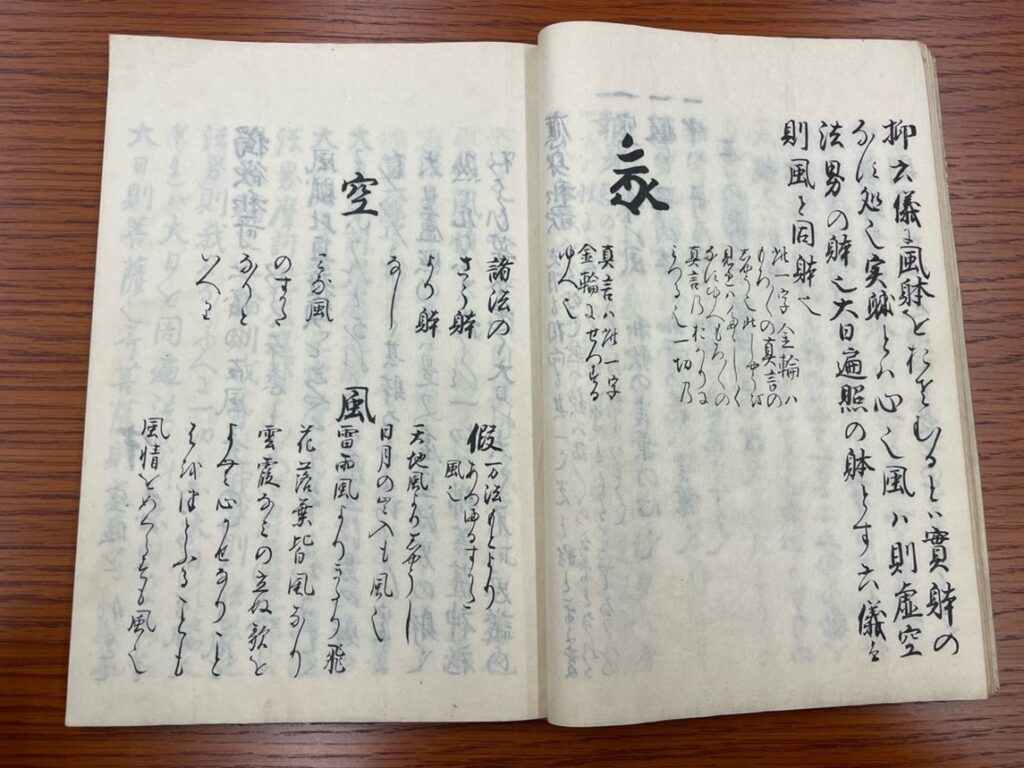

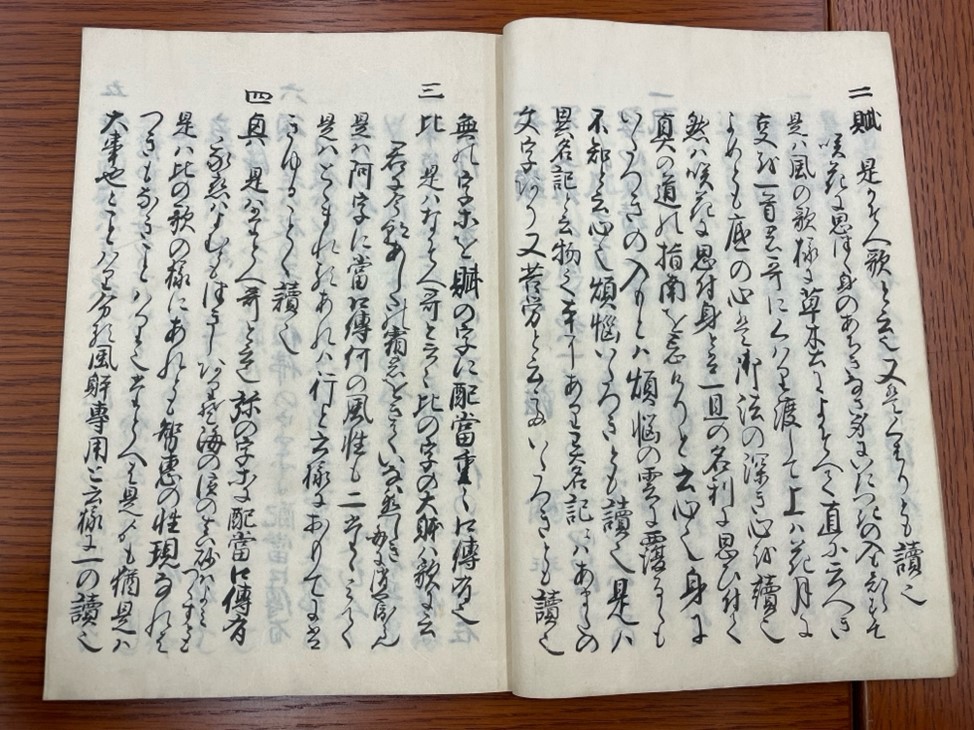

One might wonder why a manuscript would be necessary to learn how to write poetry. The answer lies in the fact that waka was much more than a poetic form; it held communicative and religious significance. After becoming the dominant literary form in the imperial court during the Heian period, waka served as a primary mode of exchange between aristocrats and elites, often reflecting nuanced emotions and complex relationships that could not be directly expressed. The art of waka required mastery of intricate poetic rules and the skillful use of seasonal and literary symbols—symbols that one had to study to use properly. For instance, as seen in figure 2, characters like “空sora; kara” (in modern Japanese, meaning “sky,” “air,” or “emptiness,” among others) and “風kaze” (meaning “wind” or “custom”) had multiple definitions and subtle meanings, depending on context. These words also carried specific pronunciations in aesthetic poetic singing. Waka kanjō offers a rich repository of references and annotations, facilitating diplomacy and courtship through poetic language.

Figure 2. One of the pages instructing the symbolic definitions (on the left page); a mandala symbol with annotation (on the right)

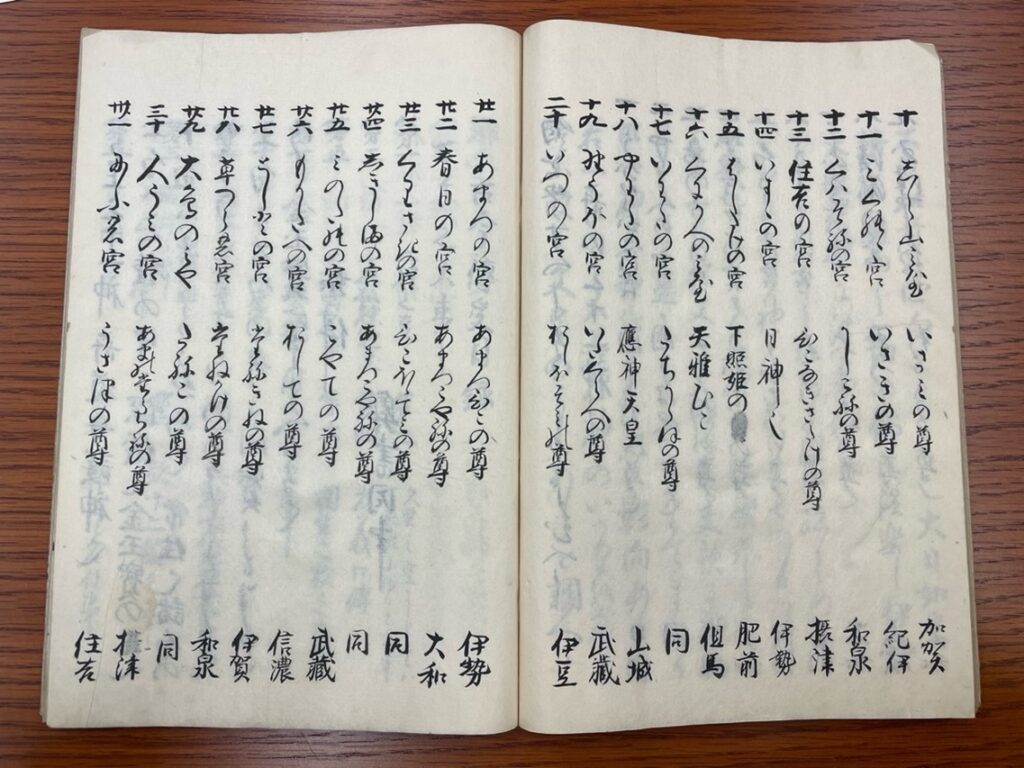

Beyond its secular functions, waka also served as a site of convergence between literature and religion. Poets frequently used waka to meditate on the transient beauty of nature as a metaphor for the cycle of birth and death, resonating with Buddhist themes of impermanence, suffering, and metaphysical reflection. These themes, sometimes communicated through ritualistic symbols like the mandala (figure 2), added layers of meaning for poets to master. Additionally, Japanese folk religion inspired waka, as seen in Waka kanjō, where a record of 31 spirits and deities (figure 3) is linked to specific regions and sites. Skillfully deploying these figures and their symbols in one’s poetry would have invoked the meanings and powers they embodied. Likewise, in the refined culture of the high court, learning to read, write, and practice waka correctly required proper guidance.

Figure 3. Record of 31 poetic spirits and deities in Waka kanjō. These pages detailed the tenth to the thirty-first.

Read vertically, they show the numerical count (top), full name, and associated regionality or site (bottom)

With waka’s thousand-year history, several poetic schools emerged, often tied to feudal aristocratic families and their domains. These regions, with their unique landscapes, customs, and histories, generated distinct schools and traditions of waka composition, and sometimes their developments were entangled in political dynamics. Poetry contests thus served as a site not only to demonstrate one’s artistic refinement and sociocultural sophistication but also to compete without military force.

Figure 4. The first page of Waka kanjō and cosmetics. Each section is clearly titled. Here we can identify the following pages belonging to “waka kanjō no maki.” Another lengthy section, “Kokin denjū or Kokin transmission,” contains an exclusive interpretation of the imperial anthology classic, Kokin wakashū

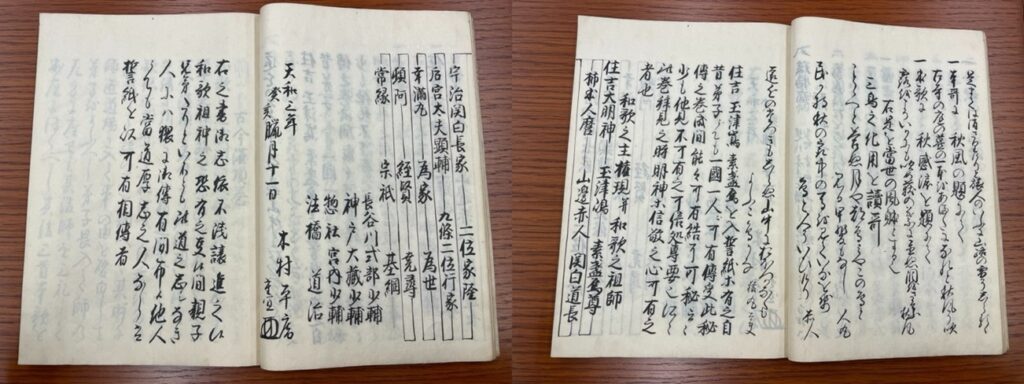

Certain “waka secrets” were passed down within specific poetic schools or families. These secrets often involved specialized knowledge of composition, interpretation, and aesthetic principles, including how to read canonical texts, select and juxtapose words, convey layered meanings, and evoke specific emotional responses. Such teachings were transmitted privately from master poets to their disciples, ensuring that the mastery of waka remained exclusive. This transmission occurred in ritualized settings, where masters shared esoteric knowledge orally or through carefully guarded manuscripts. Disciples had to learn not only the secrets but also the lineage of their school and how to properly train future students. Figure 5 shows a “family tree” of master poets, beginning with Sumiyoshi Daimyōjin 住吉大明神, the patron deity of waka poetry, and including legendary poets such as Kakinomoto no Hitomaro 柿本人麿 and Yamabe no Akahito 山邊赤人.

Figure 5. “Family Tree” of master poets, continuing over pages

Was Waka kanjō one of these coveted secret manuscripts? Possibly. However, its wide-ranging content suggests it was more like a textbook. The first section of the manuscript provides a general history, detailing the mystic origins of waka kanjō and the evolution of its rituals. Yet, as shown in figure 6, the manuscript offers invaluable, step-by-step accounts of how to conduct kanjō ceremonies. As mentioned earlier, becoming a disciple of a waka school was akin to joining a sect, and kanjō ceremonies were initiation rites involving intricate procedures, each imbued with spiritual and artistic meaning. Waka kanjō deciphers these mysteries.

Figure 6. Kanjō (initiation; ascension) ceremony procedures

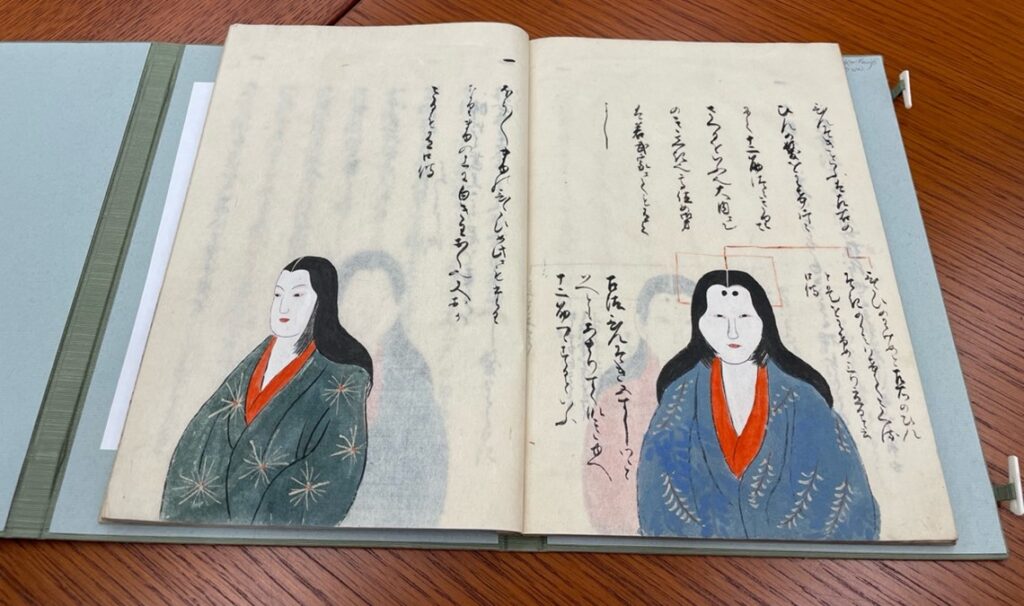

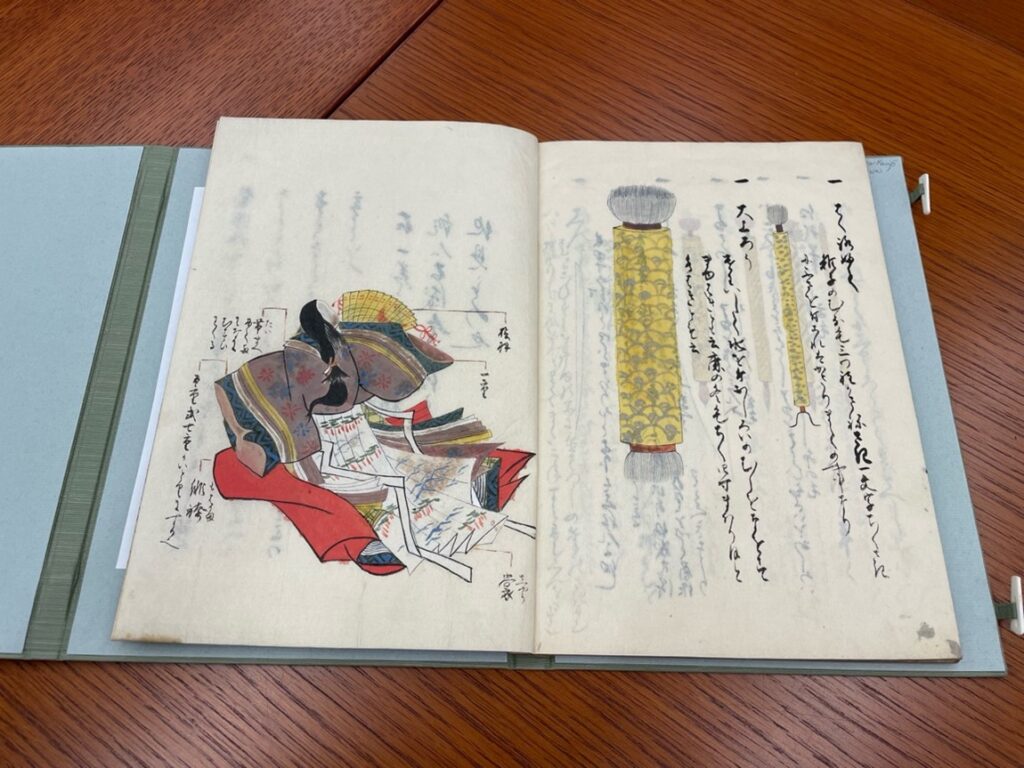

Finally, let us not forget that the manuscript is titled Waka kanjō and cosmetics. The second part, unrelated to waka, covers court ladies’ makeup, hairstyles, fashion tools, and statement items. This section, about 12 leaves long, contrasts sharply with the first part. While the first section is written in a single-style handwriting, the second is filled with elaborate illustrations, richly colored and adorned with gold and metallic pigments. Despite the shift in content, the handwriting in the text explanations suggests that the same author wrote both sections. In figure 7, we see instructions for a hikimayu technique, a circular eyebrow sculpting style that corresponds to a lady’s 5:5 hair parting and flowing hairlines. We also learn that eyebrow shape and position could indicate age, rank, and the occasion being attended. After the section on eyebrows, the manuscript details hairstyles and full attire (figure 8).

Beyond its disjointed content, Waka kanjō and cosmetics raises many questions. A passage on the final page states that all the information included is secret and should not be shared. Why? Was the manuscript intended for an exclusive audience of court ladies hoping to learn the art of waka along with how to dress the part? Or, given its seventeenth-century date (c. 1683), was Kimura trying to commercialize what was once highly coveted imperial knowledge? Who would have been the intended customers for such a luxurious and specific manuscript? And would its sale have been considered sacrilegious? These questions prompt us to mull over the possibly changed status and implications of waka, its initiation rituals, and the role of court culture on the cusp of Japan’s modern era.

Figure 7. Eyebrow Sculpting

Figure 8. Illustration of full attire and part names (left); makeup brushes and their uses explained (right)