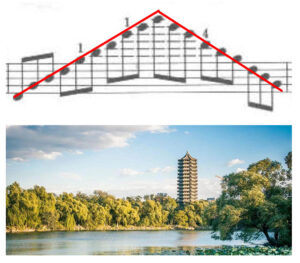

Wang Kang has long held a fascination with the concept of infinity and its embodiment in music and nature. “In music, I think some high pitches between the bass notes seem to lead us to a higher realm. The notes are like a tower on the stave, just as the top of a pagoda reaches for the infinite sky. One can see it with eyes, hear it with ears, and also imagine it with the mind. In nature, when I look at a starry sky, I can feel the infinity of the universe, silent, but bright.”

Wang Kang has long held a fascination with the concept of infinity and its embodiment in music and nature. “In music, I think some high pitches between the bass notes seem to lead us to a higher realm. The notes are like a tower on the stave, just as the top of a pagoda reaches for the infinite sky. One can see it with eyes, hear it with ears, and also imagine it with the mind. In nature, when I look at a starry sky, I can feel the infinity of the universe, silent, but bright.”

As a graduate student, he also found the embodiment of infinity in Buddhist scriptures. He recalls his first postgraduate course on a famous patriarch of the first Chinese Buddhist sect, Tiantai: “That’s the first time I met the Nirvana Sutra. Although I later took many courses on different scriptures, I found myself coming back to it.” The concepts originating from the Nirvana Sutra resonated with him: “Nirvana is a kind of infinity – one cannot use any language to describe it exactly. The only way to Nirvana is through practice and wisdom.”

As a doctoral student at Peking University, he is writing his dissertation on new descriptions of the afterlife brought by Buddhism to China in the period of Sixteen Kingdoms and Northern Dynasties. He analyzes concepts of the afterlife from the perspectives of intellectual history, history of ideas and social history, to explore how and why the concepts took root and became widespread, both among the intellectual elite and everyday people. “The relationship of these three perspectives is like a mountain – the summit is intellectual history, representing the highest degree of Buddhist thought. The valley of the mountain is the history of ideas. Social history is the base from which the upper two parts are built.”

Although intellectual elites and common people may have had different concerns – the former focused more on Nirvana, and the latter, believing they could not get to Nirvana within their lifetime, more concerned about getting to a better place (tian or heaven), Wang notes, “their actions to get to the different places are similar – such as doing good deeds, or other practices. We can look at their actual practices to find a connection of the three parts [intellectual history, history of ideas, and social history].”

Although intellectual elites and common people may have had different concerns – the former focused more on Nirvana, and the latter, believing they could not get to Nirvana within their lifetime, more concerned about getting to a better place (tian or heaven), Wang notes, “their actions to get to the different places are similar – such as doing good deeds, or other practices. We can look at their actual practices to find a connection of the three parts [intellectual history, history of ideas, and social history].”

As a participant in HYI’s training program on “Buddhism and Ethnicity in the Period of Sixteen Kingdoms and Northern Dynasties,” held at Peking University in 2019, Wang found his horizons opened greatly: “I have a more comprehensive understanding of Buddhism. Combined with the recent dramatic changes [due to covid-19], I have more macro thinking and want to grasp real, vital questions nowadays. I then want to return to the classic texts and history to find similar situations and learn from them.”

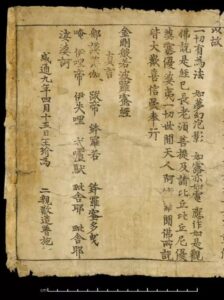

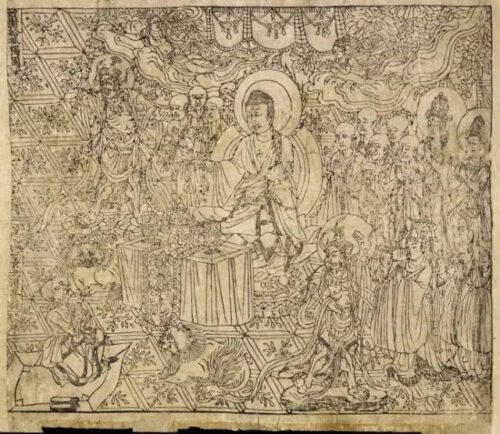

The challenges brought by the global pandemic in 2020 have led Wang to reflect on his field and the humanities more broadly: “After the pandemic, the situation is severe for humanities, especially my field, to survive. I’m also very interested in new technology and other things that represent our new digital age.” Stuck at home with his university campus shut down, Wang turned to thinking about the development of Buddhism in the 21st century. “Throughout its history in China, Buddhism has been a promoter and even leader of advanced arts and technologies. Painting technology, one of the most important technologies in ancient China, may have been driven mainly by the demand for copies of Buddhist images, mantras and scriptures. People would carry them around or would have them sent to others for blessing. This demand pushed the technology to meet it.”

The challenges brought by the global pandemic in 2020 have led Wang to reflect on his field and the humanities more broadly: “After the pandemic, the situation is severe for humanities, especially my field, to survive. I’m also very interested in new technology and other things that represent our new digital age.” Stuck at home with his university campus shut down, Wang turned to thinking about the development of Buddhism in the 21st century. “Throughout its history in China, Buddhism has been a promoter and even leader of advanced arts and technologies. Painting technology, one of the most important technologies in ancient China, may have been driven mainly by the demand for copies of Buddhist images, mantras and scriptures. People would carry them around or would have them sent to others for blessing. This demand pushed the technology to meet it.”

Wang sees an opportunity for technology to help provide modern translations of Buddhist scriptures, which have been translated into classical Chinese but are not easily understood by most Chinese people today. “We want to provide a platform for everyone to read understandable sutras in an enjoyable way. We could use artificial intelligence to translate the sutras, and works could be translated and revised online constantly by scholars in the field.” He sees a parallel with how the translations into classical Chinese were made: “The authority of the classical translation is based on the authority of maybe hundreds of people in China. They were supported by the emperor or other wealthy people to translate sutras. They usually formed a community to do the translation work. Today we could repeat their work at a larger scale and over a longer time through the internet, with the help of sophisticated AI translation which can take in criticism and constantly improve itself.”

With the translation and interpretation of scriptures in ancient China, several Buddhist schools and sects emerged, created by masters who were highly familiar with the knowledge of their time. Wang hopes that modern translations of scriptures could also lead to new developments, in part by drawing in scholars from other fields outside the humanities, including science and engineering. “They may see something that we cannot see from the humanities. After providing relatively understandable Buddhist scriptures for people from all walks of life, could this lead to a next wave of Buddhist schools and sects?”

Wang also sees ways for Buddhist beliefs and practices to be incorporated into art and media, just as in the past. “Buddhism has left many artistic achievements, including the Dunhuang grottoes and murals, which are the concrete embodiment of Buddhist beliefs and practices at that time.” He sees the chance for these practices to be revived in the context of film, video games, and virtual reality. Wang believes that numerous stories from the scriptures, if translated into modern language, could be incorporated into the experience. “People could experience the vitality of the scriptures in new ways. For example, we could use VR to construct the Pure Land virtually. Users may then feel as if they are a part of it, and could chant the name of Buddha more wholeheartedly.”

Wang also sees ways for Buddhist beliefs and practices to be incorporated into art and media, just as in the past. “Buddhism has left many artistic achievements, including the Dunhuang grottoes and murals, which are the concrete embodiment of Buddhist beliefs and practices at that time.” He sees the chance for these practices to be revived in the context of film, video games, and virtual reality. Wang believes that numerous stories from the scriptures, if translated into modern language, could be incorporated into the experience. “People could experience the vitality of the scriptures in new ways. For example, we could use VR to construct the Pure Land virtually. Users may then feel as if they are a part of it, and could chant the name of Buddha more wholeheartedly.”

Although it may seem novel, Wang notes that these developments would be following a long-standing path: “We are doing the same thing as the ancient people – they just didn’t have the technology we do. We would be using contemporary technology to show the real spirit of Buddhism. There is a term in Buddhism called 善巧方便 or upāya-kauśalya (skillful means), which means you can use the contemporary and local ways to present the true meaning of the Buddha.”

Related Stories

Announcements

HYI Scholar Eiko Kawamura awarded Prize in Classical Japanese Literary ScholarshipMonday, November 4, 2024