Hoang-Yen Nguyen’s interest in Vietnamese traditional culture and Chinese culture began at an early age – “When I was young, I lived in a suburb of Hanoi in a house that was over 100 years old. There were a lot of couplets (對聯) and horizontal tablets (匾額) in the old house. Although I was very young, I was curious about what they meant and often asked my grandfather. He simply explained the rough meaning to me and I was told that because I was a girl, I didn’t need to know very clearly. When I was a bit older, I found out that our family genealogy book (家譜) was kept in a private wooden box. I saw my grandfather open it once, but because I was a girl, I could not look at these materials. I was really very curious about what they were.” She remained undeterred and later, when living in central Hanoi, she started learning Chinese at high school. As an undergraduate, she continued to study Chinese language and culture: “There are so many Vietnamese literary works written in Chinese. I chose to study Chinese language and culture not only to understand more about China, but to learn more about Vietnamese literature too.”

Hoang-Yen Nguyen’s interest in Vietnamese traditional culture and Chinese culture began at an early age – “When I was young, I lived in a suburb of Hanoi in a house that was over 100 years old. There were a lot of couplets (對聯) and horizontal tablets (匾額) in the old house. Although I was very young, I was curious about what they meant and often asked my grandfather. He simply explained the rough meaning to me and I was told that because I was a girl, I didn’t need to know very clearly. When I was a bit older, I found out that our family genealogy book (家譜) was kept in a private wooden box. I saw my grandfather open it once, but because I was a girl, I could not look at these materials. I was really very curious about what they were.” She remained undeterred and later, when living in central Hanoi, she started learning Chinese at high school. As an undergraduate, she continued to study Chinese language and culture: “There are so many Vietnamese literary works written in Chinese. I chose to study Chinese language and culture not only to understand more about China, but to learn more about Vietnamese literature too.”

Prof. Nguyen then went to Taiwan for her MA and PhD, focusing on comparative studies of Vietnamese and Chinese traditional literature. Her PhD dissertation looked at Vietnamese envoys’ travel writing to China, in particular from 1849 to 1877, a very turbulent time in Vietnamese history. In reading the envoys’ documents, she found that they also often wrote about the Korean envoys they encountered in China.

Having long wanted to do comparative studies between Vietnam and other East Asian countries, Nguyen found herself intrigued by perceptions of the Other – “how the way we perceive and think about others affects our lives.” In particular, she was interested in Vietnamese and Korean envoys’ early perceptions – “I wanted to understand more, from the very beginning, when the Vietnamese and Koreans first saw the West, how they thought about it and how it affected their future.”

Having long wanted to do comparative studies between Vietnam and other East Asian countries, Nguyen found herself intrigued by perceptions of the Other – “how the way we perceive and think about others affects our lives.” In particular, she was interested in Vietnamese and Korean envoys’ early perceptions – “I wanted to understand more, from the very beginning, when the Vietnamese and Koreans first saw the West, how they thought about it and how it affected their future.”

While at the Harvard-Yenching Institute, Prof. Nguyen is working on a project entitled “The West Threat Perceptions in Sinographic Cosmopolis: A Comparative Study between Vietnamese and Korean Envoys to China in the 19th Century.” By analyzing the envoys’ travel writings, she aims to discover differences in how they viewed the West. “For the Vietnamese envoys, they had direct contact with the West in the beginning, because many Western countries, such as France, Holland and Spain, went directly to Vietnam for missionary work and trading. For Korea, they knew the West as a whole, but before the 19th century didn’t have direct contact with the West – they met the West and learned about its customs in China.” Prof. Nguyen finds reflections of these differences in the envoys’ travel writings: “The way they perceived the Western countries, and the way they perceived Catholicism and missionaries, is very different. For Vietnam, the envoys did not have a very good perception about the missionaries. But the Korean envoys, who met the Westerners in Beijing, were more curious and interested in churches and Western objects.”

While at the Harvard-Yenching Institute, Prof. Nguyen is working on a project entitled “The West Threat Perceptions in Sinographic Cosmopolis: A Comparative Study between Vietnamese and Korean Envoys to China in the 19th Century.” By analyzing the envoys’ travel writings, she aims to discover differences in how they viewed the West. “For the Vietnamese envoys, they had direct contact with the West in the beginning, because many Western countries, such as France, Holland and Spain, went directly to Vietnam for missionary work and trading. For Korea, they knew the West as a whole, but before the 19th century didn’t have direct contact with the West – they met the West and learned about its customs in China.” Prof. Nguyen finds reflections of these differences in the envoys’ travel writings: “The way they perceived the Western countries, and the way they perceived Catholicism and missionaries, is very different. For Vietnam, the envoys did not have a very good perception about the missionaries. But the Korean envoys, who met the Westerners in Beijing, were more curious and interested in churches and Western objects.”

The travel documents which Prof. Nguyen uses for her research are stored at institutions around the world. Although much of the Vietnamese envoy travel writing has been collected at the Institute of Sino-Nôm Studies in Hanoi, there are also collections at libraries in the United States, England and France. Prof. Nguyen has gone to great efforts to collect previously unpublished documents, and would like to make them more accessible: “I hope in the future I can translate them into modern Vietnamese so more people can read them.” She believes that these documents can shed light not just on the 19th century envoys’ thoughts and beliefs, but on how they have shaped us today: “When we get to understand the past, we can understand more about what is happening in modern life. People may think I am living in the past, but it’s very interesting to me to know how our ancestors thought about other things. It can tell us a lot.”

Image sources:

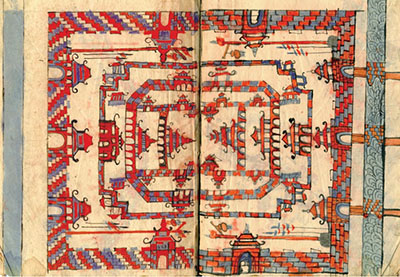

- Image of the Forbidden City 紫禁城 in Nguyễn Huy Oánh’s travel writing to Peking, “The Diary to Peking” 燕軺日程 (in 1765, 1766). Photo source: book image from The Collections of Vietnamese Envoys’ Travel Writings in Chinese (Collected in Vietnam) (越南漢文燕行文献集成(越南所藏編) ), vol. 24, p.166.

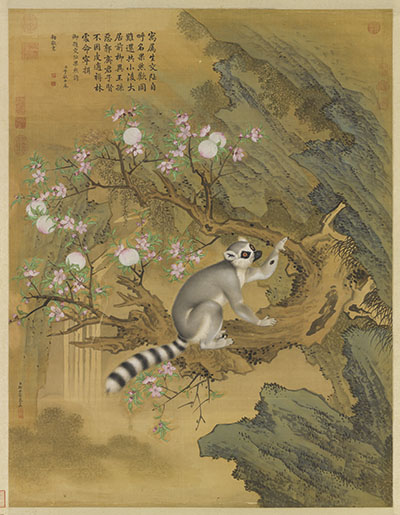

- Annam’s exotic animal presented to the Qianlong Emperor by Vietnamese missions in 1761, drawn by Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766, 郎世寧, painter of Qing Dynasty). Photo source: National Palace Museum in Taipei, file number: K2A000799N000000000PAA, available online via https://theme.npm.edu.tw/opendata/DigitImageSets.aspx?sNo=04017424

Related Stories

Announcements

HYI Scholar Eiko Kawamura awarded Prize in Classical Japanese Literary ScholarshipMonday, November 4, 2024