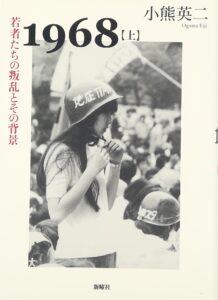

Eiji Oguma 小熊英二

Tokyo: Shinyo-sha 新曜社, 2009, 1091 pages (vol. 1) and 1011 pages (vol. 2)

Resurgence of the Sixties in 21st Century Japan

Reviewed by Kosugi Ryoko (Ph.D. candidate, Tohoku University; HYI Visiting Fellow)

In the late 1960s, Japan witnessed a large-scale “youth revolt” similar to that of the United States, West Germany, Mexico, Poland, and other several countries, where university students also played a prominent role. Although the youth revolt swept Japan and caught nation-wide attention, scholarship on this topic is strikingly thin. We can guess some reasons for this: the student violence was so intense that the youth revolt resembled a kind of mass hysteria, the emphasis on existential themes created a certain difficulty in talking about this issue, and violent factional infighting in the New Left traumatized both participants and observers.

However, today, more than 40 years after the climax of the youth revolt in 1968 and with some of the protagonists already dead, the Japanese have begun to look back to that period in both nostalgic and analytical ways. Eiji Oguma’s voluminous work, 1968, is an important example; nearly 20,000 copies of his books have already been sold. After the publication of this book in 2009, more than 10 other books on the Japanese 1960s were published by the end of 2010. Most of them are participants’ personal memoirs (Asahi Shimbun December 4, 2010).

Based on articles in newspapers and magazines, reminiscences written by the participants, handbills, and newsletters, Eiji Oguma – a historical sociologist at Keio University and an expert of the history of ideas in postwar Japan – gives us the first detailed description of the whole process of the youth revolt in Japan in the 1960s, and concludes that the youth revolt was an collective expression of the friction between the youth and Japan’s rapid economic development in the 1960s. In 1968 vol.1, Oguma starts with a series of events from the late 50s to the mid-60s that built up to the youth revolt of the late 1960s: the birth of the New Left in the late 50s, their participation in the Anti-U.S.-Japan Security Treaty Movement in 1960s, the hproliferation of the factions within them after 1960, and the emergence of campus struggles in 1965. Then, he describes a sequence of street demonstrations called Gekidou No Shichi-kagetsu (Turbulent Seven Months) from October 1967 to April 1968. In these demonstrations, students militantly protested against the Japanese government’s policy on the Vietnam War. This turned out to be a preliminary stage for the Zenkyoto Movement at Nihon University and the University of Tokyo from 1968 to 1969, the latter of which is Oguma’s main focus.

At the University of Tokyo, the struggle began with the medical students’ effort to demand the abolition of the intern system. The oppressive attitude of the administration then evoked a university-wide controversy. In July 1968, students formed Zenkyoto, an abbreviation of Zengaku Kyoto Kaigi (All-Campus Joint Struggle League). As the struggle wore on, the Zenkyoto gradually radicalized and began to question the foundations of Japanese society. The later Zenkyoto put forth slogans such as “Jiko Hitei (Self Negation)” and “Daigaku Kaitai (Break Up the University).” Finally, the Zenkyoto students occupied the entire main campus for more than six months until in January 1969, the riot police removed them from the campus. In Oguma’s view, although the University of Tokyo Struggle was virtually over at this point, the Zenkyoto style of struggle spread across Japan. Its organizational pattern, including the name Zenkyoto, its basic ideas, slogans, and strategies were replicated at a number of colleges.

Oguma pays special attention to the slogan of “Self Negation.” This meant that students should negate their status as elites, and search instead for a new subjectivity to change the university and Japanese society. He sees the Japanese students’ self criticism and their search for new subjectivity as a result of “ Gendai-teki Fuko (a new type of alienation).” By this phrase, Oguma refers to such nonmaterial suffering as a sense of emptiness and the lack of reality that youth often feel in developed and high capitalistic societies. This alienation may take the form of slash syndrome, anorexia, or nihilism in contemporary society. In the 1960s, Japan was experiencing rapid economic expansion and industrialization. Oguma states that Japanese youth at the time began to suffer from a new type of alienation, which some of them chose to express through radical student movements.

In 1968 vol.2 Oguma focuses on what became of the youth revolt as an expression of a new type of alienation from 1969 to the early 1970s. He touches on high school protests, the New Left factions’ seizure and decline of the Zenkyoto Movements, the shift of young activists’ interest toward minorities, the anti-Vietnam War movement, the factional disputes within the New Left involving murders and lynching, and the birth of the women’s liberation movement. However, above all, in Oguma’s view, the most important legacy of the youth revolt was that young people adapted themselves to the rapid economic development and the mass consumption society which had caused the revolt. In other words, through the struggle against rapid development, the youth unconsciously adjusted to the very society they had criticized.

Oguma’s conclusion is controversial and open to further discussion. For example, memoirs and reportage note that the participants in the youth revolt frequently maintained the progressive political attitudes that they developed during the 1960s, even after they left campus, and that they remain politically active in their middle and old age. Does not Oguma underestimate the students’ abiding aspiration toward social change? Moreover, it is known that participants in social movements sometimes simultaneously seek both internal and external change, for example in identity politics. Did “Self Negation” mean to the students precisely what Oguma interprets? Although we may criticize his interpretation, Oguma’s 1968 is a significant scholarly work that finally opened up space for Japanese to discuss the previously neglected 1960s.